Lightweight Memory Protection on an ARM Microcontroller

21 May 2019

For my real-time operating systems course at UT Austin, I decided to explore memory protection on an embedded system. I was interested in understanding memory protection hardware ever since working on my homegrown OS project. In this project, I went a step further and aimed to implement memory protection while minimizing context switch overhead. Below is a writeup of the project – I hope you find it interesting!

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Design

- Internal Fragmentation

- Evaluation

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Links

- Footnotes

Abstract

In a multi-tasking embedded operating system, it’s important to guarantee complete isolation of individual tasks. This is provided in part by the “virtualization” of the CPU: tasks are written as monolithic programs which depend on the OS to fairly share compute resources among all tasks in the system. In effect, a knowledge barrier is put in place between tasks that helps simplify the process of designing complex systems. In an ideal world, these tasks could not interact with one another except through explicit synchronization channels; in reality, however, tasks are able to tamper with each other’s memory, since all share the same address space. Additional hardware is needed to strengthen isolation guarantees and prevent tasks from reading and writing one another’s private data. The Memory Protection Unit (MPU) is a peripheral common to most modern processors including the TM4C123G. In this blog post, I will describe how I have leveraged the TM4C123G’s MPU to achieve protection of task and OS memory while minimizing additional context switch overhead. Loaded processes’ code, data, stack(s) and heap are protected from other tasks, and OS memory is protected from loaded processes. Tasks compiled with the OS are able to access OS code and global data in order to execute, but are still isolated from one another. My implementation can mutually isolate up to twenty-nine foreground tasks with a 16KB heap.

Introduction

Background

Memory protection is provided in most computers by the Memory Management Unit or MMU. This hardware unit also enables virtualization of the address space. In more resource-constrained systems, the MMU is left out in favor of a Memory Protection Unit or MPU. While the MPU cannot virtualize the address space, it can at least enforce access policies around bounded regions of memory that the OS defines.

Motivation

Leveraging the MPU can strengthen the OS’s guarantee of isolation between tasks, but its usage comes at a cost. The MPU is typically somewhat simple in terms of its programmability. For example, the MPU in the TM4C123G features only 8 separately configurable regions. In an application with many tasks, these regions cannot fully specify the memory access policy in a global manner. Rather, the MPU needs to be reprogrammed during each context switch to reflect the context the CPU is about to enter. The additional cycles spent doing this in the context switch can be costly and inevitably take away time from tasks doing useful work.

As for a real-world example, FreeRTOS supports the use of an MPU to protect memory per-task1. However, like I mentioned, their implementation reconfigures entire regions of the MPU. Again, this must be done every context switch which steals time away from tasks doing productive work.

Some time penalty in the context switch when using the MPU is unavoidable. But, this does not mean steps cannot be taken to minimize the time spent re-configuring the MPU. We will see that certain features of the MPU in the TM4C123G allow us to configure much of the MPU once and reconfigure a small subset of parameters in the context switch.

Design

Requirements

The goal of this project is to guarantee mutual isolation and protection of tasks’ stack memory, heap memory, and process code and data. Stack-allocated variables in one task shall not be readable nor writable by any other task. Similarly, memory allocated to a task on the heap will not be readable nor writable by any other task. My design will also aim to add minimal overhead to the OS. The MPU hardware should not be massively reconfigured at every context switch.

This implementation supports loading processes from disk into RAM. Code and data of a loaded process will belong to the process control block and will be accessible to all child tasks. However, the stacks of each task in the process will remain inaccessible to one another. Also, any heap memory allocated to a process task will be accessible only to it – not to any other task in the system.

Importantly, this implementation does not protect task code if the task is compiled with the OS (i.e. not loaded as a process from disk). Tasks compiled into the OS executable are able to execute any functions that they can be linked against.

Task memory will be protected automatically upon task creation and heap allocation.

As a proof of concept, my implementation can protect memory of up to twenty-nine different tasks. It cannot scale indefinitely. This is in part due to limitations of the MPU, which imposes a limit on the number of regions that can be individually configured at one time. In a system that must support more tasks, the implementation could be changed to make protecting task memory optional, so that while only so many can be protected, more than that may run in the system.

Target Platform

My solution is implemented on an ARM Cortex-M4F-based microcontroller: the TM4C123GH6PM. It runs at 80MHz and contains 32KB of RAM. I will be implementing my solution within the OS built for my real-time operating systems course at UT Austin. The OS contains a priority-based scheduler, supports synchronization primitives such as semaphores, and provides a simpler command prompt over the UART interface to interact with the system. Tasks are run as unprivileged code and must use the SVC call interface to execute system calls. Importantly, the OS does not provide any virtualization of memory since there is no Memory Management Unit (MMU) present in the system. The system does, however, provide a Memory Protection Unit (MPU) which can be used to protect memory despite the lack of virtualization.

MPU Functionality

The MPU is a hardware unit used to protect regions of memory. The MPU of the TM4C123GH6PM supports up to eight configurable memory regions. Each region is configured with a base address, size, and permissions for both privileged and unprivileged access. The region’s base address must be aligned to the size of the region. Each region is further divided into eight equally-sized subregions which can be individually enabled or disabled. My design will leverage subregions heavily to maximize the number of tasks that can be mutually isolated.

The MPU implements relative priority between regions. Regions are indexed 0 to 7 where a higher index indicates priority over lower indices. For a given memory access, the MPU region with the highest index containing the relevant address will be used to authorize the access. If a subregion is disabled, the access will instead be evaluated by the next lowest priority region that overlaps and is enabled. If the MPU is turned on and a memory access maps to none of its regions, the access is denied.

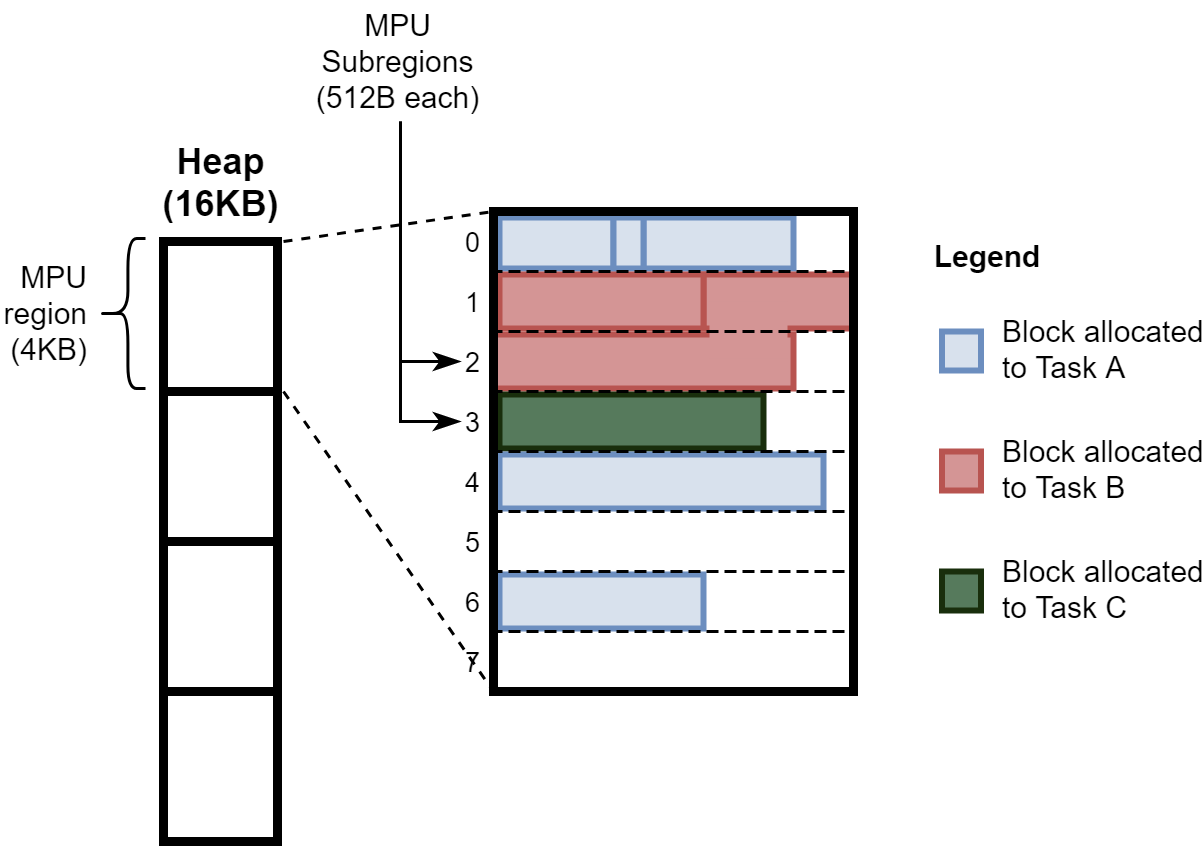

Heap Protection

The heap is implemented as a simple Knuth heap with some changes to accomodate the MPU. Any memory allocated to a task on the heap is guaranteed to be isolated from other tasks. This is achieved by grouping memory allocations together into MPU subregions by the owner task. When tasks are allocated memory, the heap manager associates the task with all MPU subregions touched by the allocated block. The task now “owns” those subregions, and no other task will be allocated memory in those subregions. In this way, the heap manager guarantees that every subregion will contain blocks belonging to at most one task. When the last allocated block in a given subregion is freed, the owner task relinquishes ownership of the subregion, and the heap manager is free to allocate memory in that subregion to another task. At this point, protecting the heap is as simple as prohibiting access to heap subregions that the running task doesn’t “own”.

A naive solution would be to statically partition the heap into equal-size pieces and allocate one to each task in the system. However, the approach I have chosen ought to scale better to systems where tasks may vary in their demand for heap memory. For example, if only half of all tasks use the heap, then any blocks statically allocated to the other tasks would go unused – a huge waste. In the case where the number of tasks in the system is maximized and all demand heap memory, my solution will allocate each a subregion and converge to the simpler approach.

Figure 1 shows an example heap where three tasks have each been allocated memory. Each subregion will contain memory for at most one task. It’s possible for a task’s memory to span multiple subregions, as in subregions 1 and 2. This design is susceptible to some amount of internal and external fragmentation, though less than the naive solution I described earlier. You can see internal fragmentation at the end of subregion 0. Only small allocations can fit in the remaining free space of subregion 0, and they must be allocated to Task A to be put there in the first place (since Task A has claimed that subregion). As for external fragmentation, suppose Task C were to request 256 Bytes from the heap manager – this is larger than one subregion. For that reason, the allocation could not fit in the empty subregion 5. It would instead be placed in subregions 7 and 8, leaving subregion 5 to go to waste until a small enough block could be allocated there.

Stack Protection

To protect tasks’ stack memory, I simply allocate stack memory on the heap and tell the heap manager that it belongs to the relevant task. This approach is more flexible than a stack pool, where stacks of a certain maximum size must be statically allocated, which can lead to wasted memory.

Fragmentation

As discussed previously, this design exhibits some amount of internal and external fragmentation. Here we will discuss the net effect of fragmentation and ways of addressing it.

Internal Fragmentation

The design exhibits internal fragmentation when a task requests more memory than can fit in the remaining free space in a subregion it already owns. The heap manager will go allocate another subregion to the task, or worse, will fail to allocate memory, leaving the hole in the first subregion to go to waste.

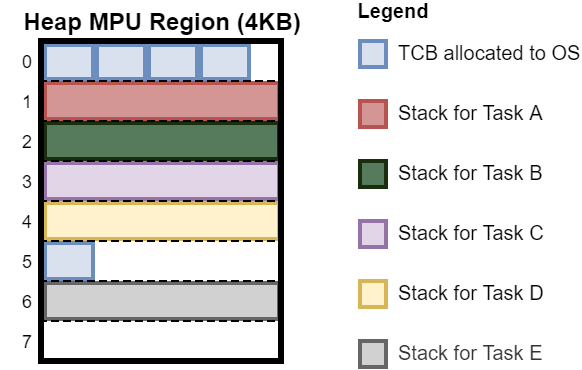

This is particularly noticeable in systems that spawn many threads. The OS itself is allocated memory on the heap as needed for TCBs. This memory is protected just like any other heap memory, which means the OS is allocated MPU subregions. Immediately after allocating space for the TCB, space is allocated for the task stack. This means that the OS’s MPU subregion will be followed by a task’s MPU subregion, since the heap manager allocates subregions sequentially. This means that as the OS fills up its subregion, it is likely to experience internal fragmentation. See Figure 3 for an illustration of the problem.

This can be solved by pre-allocating a pool of TCBs for the OS to pull from at initialization. By allocating all TCBs at once, the programmer will force all OS subregions to be adjacent. This will reduce internal fragmentation since allocated blocks are allowed to span the boundaries between adjacent subregions as long as both belong to the same entity. This requires knowledge of the target application and how many tasks it will require.

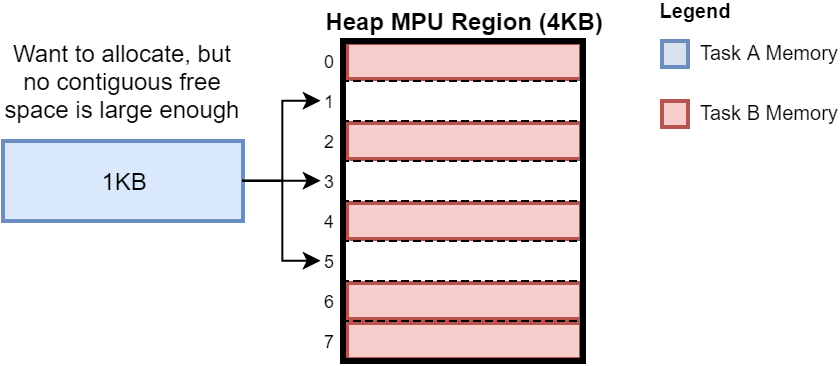

External Fragmentation

The design exhibits external fragmentation when a task requests more memory than can fit in the free space made up of one or more free MPU subregions. This will occur when tasks free all of the memory they own in a given subregion, and the subregion becomes free while its neighboring subregions are still occupied. See Figure 4 for an illustration of the problem.

Process Loading

When a process is loaded from disk, the OS stores its code and data on the heap – we can leverage heap protection to protect these. A process can have multiple tasks which all ought to have access to the process’s code and data. However, heap memory allocated to a process task ought not to be accessible by other tasks in the same process; nor should task stacks. This suggests that tasks should be granted access to MPU subregions of the heap that belong to their parent process, and that any memory allocated specifically to the task should be placed in a subregion accessible only to it. My solution thus must be able to allocate memory to both tasks and processes, and be able to look up memory allocated to a task’s parent process in order to grant a task access to it.

Changes to TCB, PCB, and Context Switch

The TCB and PCB are expanded to include a struct of type heap_owner_t used by the heap manager to manage MPU subregions. The TCB now also contains a pointer to the base of its stack, which used to free the task stack upon killing the task. These changes are italicized in Listings 1 and 2. The contents of the heap_owner_t struct are shown in Listing 3.

typedef struct _pcb_s

{

unsigned long num_threads;

void *text;

void *data;

heap_owner_t h_o; // Added

} pcb_t;

Listing 1. The process control block (PCB) struct, with additions annotated.

typedef struct _tcb_s

{

long *sp;

struct _tcb_s *next;

uint32_t wake_time;

unsigned long id;

uint8_t priority;

uint32_t period;

unsigned long magic;

void (*task)(void);

char * task_name;

pcb_t *parent_process;

long *stack_base; // Added

heap_owner_t h_o; // Added

} tcb_t;

Listing 2. The thread control block (TCB) struct, with additions annotated.

typedef struct _heap_owner_s

{

unsigned long id;

uint32_t heap_prot_msk;

} heap_owner_t;

Listing 3. The heap_owner_t struct.

The heap_owner_t struct is a handle used by the heap manager to identify tasks and processes in the system whose memory ought to be mutually isolated. The id field uniquely identifies the memory’s owner, whether that be a task or a process. The heap manager will allow blocks with the same owner ID to be grouped together in the same subregion; blocks with different owner IDs must be placed in different subregions. The heap_prot_msk field is a mask indicating which heap subregions this task or process has memory in and therefore ought to be allowed to access.

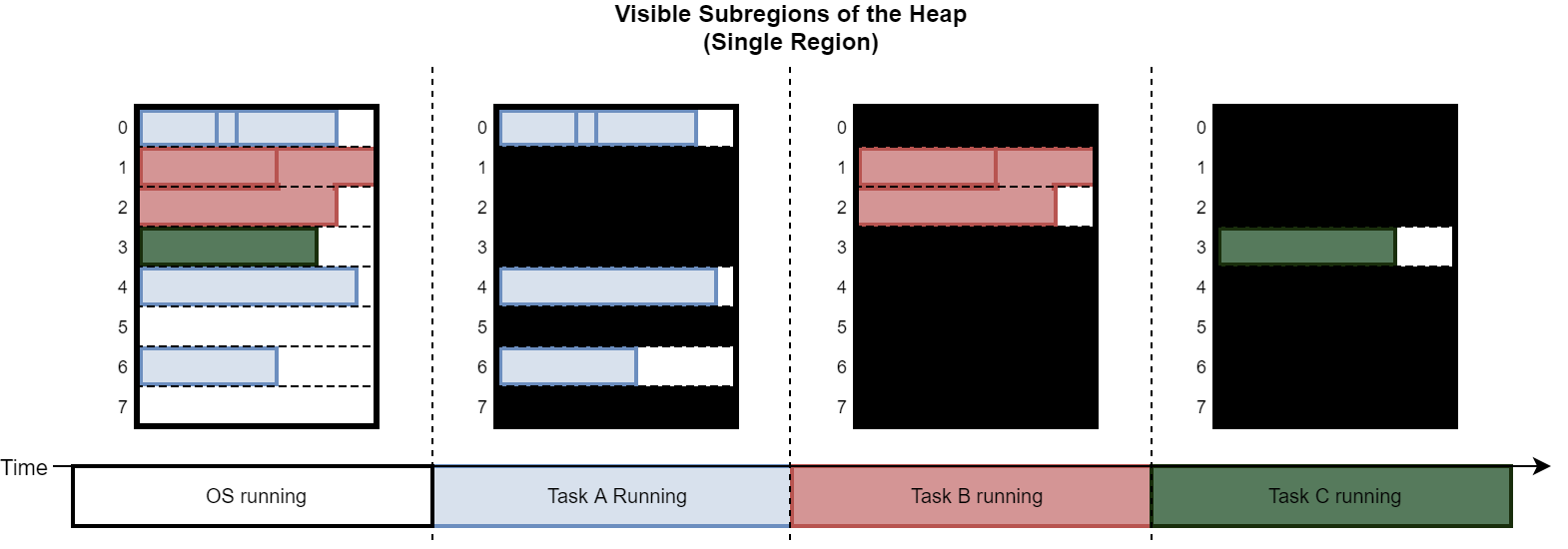

During a context switch, the OS configures the MPU to allow access only to heap subregions associated with the next running task. This is indicated by the heap_prot_msk field in the heap_owner_t struct of the TCB and parent PCB (if applicable) associated with the next task. All other subregions (either associated with other tasks or unused) are protected. The pseudo-code in Listing 4 illustrates this procedure.

u32 accessible_subregions = tcb->h_o.heap_prot_msk;

if(tcb->parent_process)

{

accessible_subregions |= tcb->parent_process->h_o.heap_prot_msk;

}

MPU_ConfigureSubregions(accessible_subregions);

Listing 4. Pseudo-code demonstrating how subregions are made accessible based on the TCB and PCB.

The MPU regions themselves do not need to be reprogrammed at each context switch. These are programmed once at initialization. Only the subregion masks for each region need to be reprogrammed during the context switch. This keeps the context switch fairly light.

Maximum Number of Tasks

The 16KB heap contains a total of thirty-two subregions. The maximum number of tasks that can be allocated is twenty-nine, as the OS will consume three subregions allocating TCBs and the rest of the subregions are allocated for task stacks.

Process Loading Subtleties

A trick is played to give the process ownership of the code and data loaded from the ELF into RAM. Because these regions are stored in the heap before the process’s PCB is created, it is impossible to malloc space for the code and data and have it belong to the process from the get-go. Instead, I spawn a new task from the interpreter whose sole job is to load the ELF. Initially, the code and data will belong to this “ELF loader” task. Then, after the PCB has been created and just before the ELF loader dies, ownership of the subregions containing the code and data are transferred from the ELF loader task to the PCB. Since the ELF loader was its own task, its heap memory is isolated from all other tasks, so we don’t need to worry about the PCB inheriting anything that it shouldn’t in those subregions.

Final MPU Region Configuration

Given the design described, MPU regions are configured as in Table 1. Region 0 (lowest priority) is configured to span the entire memory space and its policy for unprivileged code depends on the task being run. This is because the MPU must be more permissive for tasks compiled with the OS. All such tasks will have no parent process since they are started from the OS main function. Such tasks must be able to access code in flash that is mixed with the OS image – to simplify things, OS tasks are allowed to access the entire memory map, except for heap subregions allocated to the OS. For OS tasks, region 0 is configured as fully permissive. For process tasks, access to region 0 is denied.

| # | Base Addr | Size | Unprivileged Access | Privileged Access | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0x00000000 | 4GB | Varies2 | R/W | Spans address space. Applies to disabled subregions of heap. |

| 1 | 0x40000000 | 1GB | R/W | R/W | Allow all peripheral access. |

| 2 | 0xE0000000 | 1GB | R/W | R/W | Allow all peripheral access. |

| 3 | |||||

| 4 | &Heap | 4KB | Varies3 | R/W | Heap region 0 |

| 5 | &Heap+4KB | 4KB | Varies3 | R/W | Heap region 1 |

| 6 | &Heap+8KB | 4KB | Varies3 | R/W | Heap region 2 |

| 7 | &Heap+12KB | 4KB | Varies3 | R/W | Heap region 3 |

Table 1. MPU Region Configutation. Some aspects of the configuration may change at runtime depending on the current task. See footnotes for more information.

Regions 4 through 7 are configured as consecutive regions together spanning the heap, and their policy for unprivileged code also depends on the current task. An access to a disabled subregion of the heap will instead be evaluated by region 0, which must enforce the desired policy. For process tasks, region 0 will be unpermissive. Therefore, region 4-7 must be R/W permissive to unprivileged code and accessible subregions will be enabled. For OS tasks, the opposite is true: region 4-7 will be configured as unpermissive and accessible subregions will be disabled. In summary, the permissiveness for unprivileged code of region 0 and regions 4-7 are always complementary, and depend on if the task belongs to a process or not.

Evaluation

Verifying Stack Protection

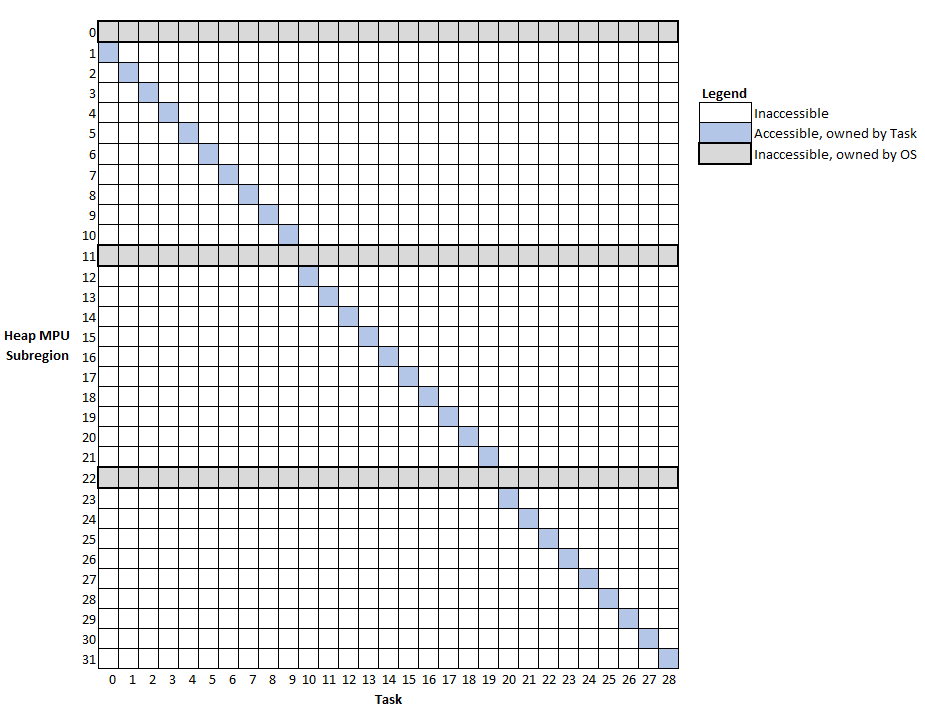

Figure 5 shows which MPU subregions of the heap are accessible to which task for a system running twenty-nine tasks. Each task is allocated a unique subregion of its own, where its stack is located. Certain subregions (marked in gray) are owned by the OS (for storing TCBs) and are not accessible to any task.

In a simpler system, I can verify that accessing another task’s stack generates a memory management fault. I spawn two OS tasks that both have access to a global integer pointer. Task A points the pointer to a local variable in its stack. Task B waits until Task A has done this and then tries to dereference the pointer to A’s stack. Listing 5 shows the tasks for this test program.

Sema4Type sema;

volatile int *volatile task_a_stack = 0;

void TaskA(void) {

volatile int x = 1;

task_a_stack = &x;

OS_bSignal(&sema); // Signal Task A to run

while (1);

}

void TaskB(void) {

OS_bWait(&sema); // Wait for Task B to signal

volatile int z = *task_a_stack; // Should generate MPU fault

}

Listing 5. Stack protection test program.

Indeed, upon running this program, one will see that a memory management fault is triggered immediately after dereferencing the pointer to Task A’s stack. My design is successful at protecting a task’s stack.

Verifying Heap Protection

Reading/Writing Another Task’s Heap Memory

Sema4Type sema;

volatile int *volatile task_a_heap = 0;

void TaskA(void) {

task_a_heap = (int*)Heap_Malloc(32);

OS_bSignal(&sema); // Signal Task A to run

while (1);

}

void TaskB(void) {

OS_bWait(&sema); // Wait for Task B to signal

volatile int z = *task_a_heap; // Should generate MPU fault

}

Listing 6. Heap protection test program (Read/Write).

We can modify Listing 5 slightly to test heap protection as shown in Listing 6. Rather than point task_a_heap at a stack variable, I assign it to the return value of Heap_Malloc. Once again, Task B encounters a memory management fault upon dereferencing the pointer.

Freeing Another Task’s Heap Memory

Sema4Type sema;

volatile int *volatile task_a_heap = 0;

void TaskA(void) {

task_a_heap = (int*)Heap_Malloc(32);

OS_bSignal(&sema); // Signal Task A to run

while (1);

}

void TaskB(void) {

OS_bWait(&sema); // Wait for Task B to signal

Heap_Free(task_a_heap); // Should generate MPU fault

}

Listing 7. Heap protection test program (Free).

With more small modifications, we can make sure that freeing another task’s memory is similarly not allowed (Listing 7). Rather than dereference the pointer to Task A’s heap memory, Task B passes it to Heap_Free. Once again, this test succeeds and the access is denied by exception.

Demonstrating Heap Flexibility

Previously, I showed that my solution supports up to twenty-nine tasks if each limits heap consumption to one subregion. However, my solution is flexible enough to allow greater consumption of the heap per-task. In a system with an idle task, a lone user task in the system with a 256 byte stack is able to acquire as much as 15072 bytes of space in the heap.

Measuring Context Switch Overhead

| Config | Context Switch Time |

|---|---|

| No Memory Protection | 1.792 microseconds |

| Memory Protection with Heavy Reconfiguration | 7.167 microseconds |

| Memory Protection with Lite Reconfiguration | 6.250 microseconds |

Table 2. Context switch duration.

In Table 2, I measure the context switch duration for no memory protection, memory protection with heavy reconfiguration, and my design: memory protection with lite reconfiguration. The implementation with heavy reconfiguration fully initializes each of the four MPU regions of the heap during each context switch. This approximates a solution in which each task and/or process in the system maintains its own set of MPU regions which must be programmed into the MPU prior to running. This is much ``heavier’’ reconfiguration than merely masking subregions of a constant region configuration as in my solution. The addition of memory protection does lengthen the context switch duration. That said, the context switch is shorter than it would otherwise be thanks to the use of subregions, which enable relatively light reconfiguration of the MPU during a context switch compared to heavier approaches. Lite reconfiguration yields a reduction in context switch duration of 12.8%.

Conclusion

Summary

In this project, I have demonstrated a low-overhead implementation of memory protection that is capable of protecting heap memory, task stacks, and process code and data in a real-time operating system.

Future Work

Addressing the Task Limit

As mentioned previously, my solution limits the number of tasks in the system to a maximum of twenty-nine. This is because the MPU uses four regions to span the heap, which yields thirty-two subregions in which to store task stacks, three of which are consumed by the OS. One way to address this is to make memory protection optional. In this scenario, the programmer is left to explicitly configure certain task stacks, memory allocations, and processes as protected. They would use discretion, enabling protection judiciously only for critical memory regions.

Supporting Shared Memory

Most operating systems must support some form of inter-process communication. Currently, two processes loaded from disk have no way to communicate with one another. One potential solution is to provide an API to the heap to allocate memory into a new subregion or subregions which will be accessible by two or more processes. Each process would specify the shared memory by an agreed upon key, say a string, in order to be granted access to it. The API would respond with a pointer to the start of the region which the processes can now use to communicate. The heap’s subregion table would need to be modified to support mapping multiple heap_owner_t structs to each subregion.

Supporting Dynamic Linking

I had considered supporting dynamic linking: a process by which the OS replaces placeholder function calls in the loaded process with the actual address of the function. After introducing protection of OS memory, this becomes slightly harder to support, but certainly possible. It just becomes necessary to isolate all OS library code into a separate region of RAM which is configured as accessible to unprivileged code, including process tasks, in the MPU. This was deemed out of scope for this project but could easily be implemented on top of my design.

Acknowledgments

The OS used for this project was built by me and my lab partner, Jeageun Jung, for our real-time OS course at UT Austin. Thank you Jeageun!

Links

The project code can be found on Github: https://github.com/rjw245/EE44M-Sp19-grad-lab-rjw2624