Absolutistic Modal Flatitude!

25 Mar 2017

I’ve been taking guitar lessons for a few months now and recently had the opportunity to combine music and programming to strengthen my understanding of music theory.

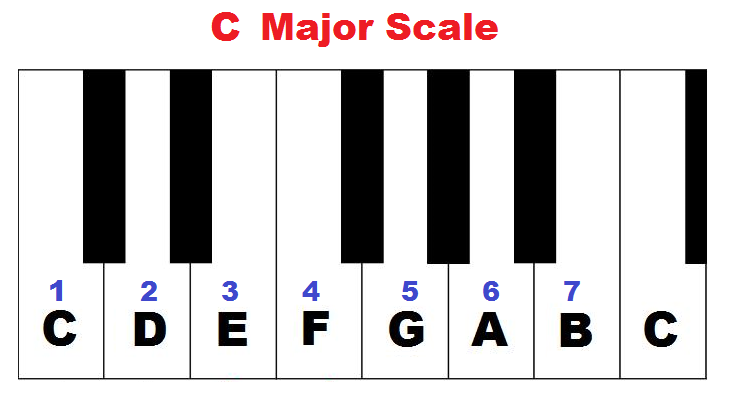

A few of my lessons focused specifically on how western scales are constructed. There are certain patterns that define these scales; one of the main patterns at play in the C major scale has to do with the distance between successive notes.

As you can see above, certain notes of the scale have an unplayed black key between them, and others don’t. The intervals where a black key is skipped are called “full steps”, and adjacent note intervals are “half steps”. What we see in the C major scale is the following interval pattern:

Full, full, half, full, full, full, half.

It’s possible to change the character of the scale by making certain notes flat. To remain a western scale, however, the above pattern must always be present somewhere in the scale (in other words, it’s okay for the pattern to rotate around). In fact, for any given scale, there will be exactly one note that can be flatted while retaining this pattern. This process of flatting particular notes is called changing the mode of the scale; subsequent modes will sound darker and darker as more notes are flatted.

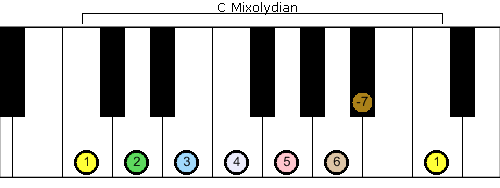

The C major scale shown above is of the Ionian mode. Flat the correct note, and we’ll find ourselves at the Mixolydian mode. Listen to the Mixolydian mode being played:

Compare the two scales on a keyboard, and you’ll notice that the 7th note has been flatted:

If you start counting intervals at the fourth note, you’ll recognize the full, full, half, full, full, full, half step pattern.

So in summary, you can move from one mode to the next by flatting the particular note which maintains the necessary interval pattern somewhere in the scale. My guitar teacher Sam Davis calls this relationship “Absolutistic Modal Flatitude”, hence the name of this post.

I wanted to prove to myself that I understood this concept, so I wrote a Python program that uses this algorithm to move between neighboring modes. You can find the source code on Github.

First I define all possible notes in the scale (aka the chromatic scale) with their frequencies (so that I can play them back):

Then I define which of those notes make up the Ionian mode. False == don’t play it, True == play it. I have a separate data structure cur_mode which tracks the mode we are currently interested in playing. We start with the Ionian mode.

Anywhere there is a False between two Trues is a full step (because we are skipping one note), and anywhere there are two adjacent Trues is a half step. It’s important to note that there there is one fewer entry in my mode data structures than in frequencies; this is because a scale concludes on the “1” note of the next octave, so we should wrap around to the first index of cur_mode when deciding whether to play this note.

I set up a while loop which will play the current mode, then tweak it to move to the next mode. First, the code which plays the scale:

It’s fairly straightforward: move through cur_mode, and play a note if the mode says it should be played. You can see where I wrap around the end of cur_mode.

Now it’s time for the really cool part: transforming the current mode into a new one. We simply locate the pattern of the Ionian mode (full-full-half-full-full-full-half) wherever it is in the current mode, and flat the seventh note of that pattern.

Eventually the note we’ll be flatting will be the root of the scale, the 1, in this case C5. For the purposes of this demonstration, we would like to keep the scale rooted in C. If we ever find that the root of the scale has changed, we simply rotate the mode pattern back one step so that we are once again playing C5 as the root:

And that’s it! If you’re curious about listening to each of the modes, you can find a link to the code above. Alternatively, you can listen to the playback below:

I had a lot of fun with this quick project and it really helped me to understand modes better. I think that in general boiling a problem down to simple logic and implementing it in code is an excellent test of how well you understand a given topic.

I hope this was an interesting read, and please let me know what you think in the comments.